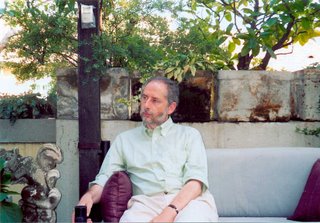

Eyewear is very glad to feature Peter Robinson (pictured here) this Friday. He is arguably one of the finest, and most subtly innovative, of lyric poets now writing in the English tradition.

Eyewear is very glad to feature Peter Robinson (pictured here) this Friday. He is arguably one of the finest, and most subtly innovative, of lyric poets now writing in the English tradition.Robinson was born in the North of England in 1953. After seventeen years teaching English Literature at various universities in Japan, he has recently accepted a chair in the School of English and American Literature at the University of Reading. He is married and has two daughters. His many publications include Selected Poems (Carcanet, 2003), a collection of aphorisms and prose poems, Untitled Deeds (Salt, 2004), and Twentieth Century Poetry: Selves and Situations (Oxford, 2005). Two new books of poetry, Ghost Characters (Shoestring) and There are Avenues (Brodie), appeared earlier this year. Forthcoming this autumn are two books of translations, The Greener Meadow: Selected Poems of Luciano Erba (Princeton) and Selected Poetry and Prose of Vittorio Sereni (Chicago), as well as a collection of his interviews, Talk about Poetry: Conversations on the Art (Shearsman). A collection of essays on his work, The Salt Companion to Peter Robinson, is scheduled for October.

Disorientation

That newly fledged hedge sparrow

that flutters in the aura

of a neon lamp among the laurels

activates this height of summer

on pools with their reflected glories

where rain, nostalgic for the sky,

evaporates as heat

relentlessly returns, and we

are suddenly that bit poorer.

Obits come from another day.

Late light glows behind the leaves;

it backs off, turns away,

and I can do no more.

Like when, just out of hospital

and trying to feel well,

you sense the place as fragile;

you see how two wood pigeons

have gone and built their nest

in branches over the garden fence,

scaring away such smaller birds

as those aligned on the top of one vast

motorway junction sign

for Canterbury, Sevenoaks, Dover and the coast

— these things themselves like a picture of health,

being more at home than you can be

in your curiously lost self-interest,

and the light too going west.

poem by Peter Robinson. First published in English (2005)

Comments