I am one of those who believes that 2005 was a very good year for all sorts of poetry published in the UK and Ireland - just look at the T.S. Eliot Prize short-list - hardly a dud there, and arguably six books that could win without much fuss over any injustice or cronyism. I'd say which book I want to win, but a handful of the poets up for it are, admittedly, friends of mine - and, in fact, I am torn a little.

I am one of those who believes that 2005 was a very good year for all sorts of poetry published in the UK and Ireland - just look at the T.S. Eliot Prize short-list - hardly a dud there, and arguably six books that could win without much fuss over any injustice or cronyism. I'd say which book I want to win, but a handful of the poets up for it are, admittedly, friends of mine - and, in fact, I am torn a little.It does seem odd that Hill's Comus was not selected, along with a few other collections, that might easily have slipped in for notice, but, since this was a bumper year, did not.

Three collections of poetry which I very much enjoyed, and did not, perhaps, receive the accolades or gongs they deserved, include two from Bloodaxe, and one from the smaller Irish press Salmon.

Sally Read gave us her debut collection early in the year. The Point Of Splitting (Bloodaxe) from its edgy title to disturbing cover onwards, is a sexy, dark and actually at times twisted exploration of eros and thanatos, with stops along the way to deal with issues such as nursing, men teaching women to load guns, and the joys of anal sex. Sensationalism aside, what struck me was the ability to shape and control the competing claims of lyricism, form, wit, and a strong, even unique, visual sense. Poems like Soldier ("Exhausted, you trace my bare arse with one idle hand") or the haunting and even unforgettable "Instruction" are very good. Read is on my list of the best new poets now emerging in the UK, and I very much look forward to her next book.

I have known the work of Kevin Higgins since meeting him briefly in New York City three or four years ago, at a poetry launch. His reading at Bob Holman's Bowery Club impressed me - he was not like other contemporary Irish poets - more louche, more savage in his wit, with less need to toe a party-line (even though political in concern at times) - in short, more in the line of Swift than Yeats and heirs (who are often a little too concerned with the sublime decorum of things). So, yes, Higgins was funny, and bold. He also writes a sort of poem that no one else does, currently. To my ear, that makes him an original - after all, the hardest thing for a poet to do is actually sound as unique as each person thinks themselves to be. Let me be clear on this - Higgins has forsaken a direct interest in form, or the lyric, to stake out territory that is far more bleak, blunt and necessary - he speaks as an angry man at the turn of a new century, one who refuses to be bought or sold, but knows the value of words that aren't simply being used for display, disguise - he is a sort of master of expressing disgust, and praising the shabby.

Just as Read takes me in to worlds no poet has before (bedrooms where men and women openly admit to their interest in weapons; rooms where nurses pack the dead away with calm and indifference) Higgins actually invents a world as much his as Greene's was to him: a compromised, dusty edge of Galway, suddenly made shiny and new by Globalism; Higgins is the voice of discontent, and his next collection, when he shifts in to a more interior key, after mapping the outer edges of a world being transformed utterly, will be a revelation, I suspect. At any rate, no other younger Irish poet has written so many visually arresting and witty poems about the New Ireland as can be found in Higgins' The Boy With No Face.

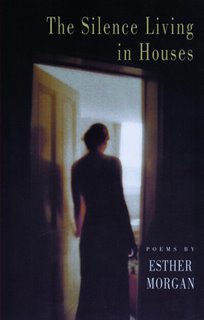

Esther Morgan, whose work I have been pleased to publish at www.nthposition.com has produced a very fine second collection, The Silence Living In Houses (cover pictured above), out from Bloodaxe. A poem like "Balancing Act" presents her lucid, elegant and disturbing voice precisely: "The blood tilts inside her head: / in a continuous present / a girl is carrying a tumbler".

I found poems like "Small-boned" and "Half Sister" chilling, eerie, haunting - of course, the book takes as one of its aspects the Gothic theme of houses haunted - by former acts, by present memories. This is a difficult sort of trope to make new, and Morgan does this. Indeed, the opening section of the book, "The House Of" is a sustained, small-boned triumph, and is especially recommended. Once again, Morgan, like Read and Higgins, stakes much on a strong visual offering to the reader. At the end of "Endurance" the house as ship is figured so: "the house rigged in ice and going down".

As Morgan says "I worry at my argument of bone" - and she does so with terrible care, alerting the reader to the sinking and the rising spirits that haunt each dwelling place, whether that be a home, or a poem. Morgan's third collection, when it comes, will almost certainly establish her, once and for all (as if more than this book was needed) as one of the best younger poets now writing in the British isles.

Comments